The perception of time is fluid; sometimes it fades away, sometimes it stands still. General theory of relativity has already taught us that time is in fact fluid. Time, and its fluidity, are the main components of Volkan Kızıltunç’s art. Through conceptual and visual research of most technologies of photography – still photography, film and video – his works also address the fluidity of medium.

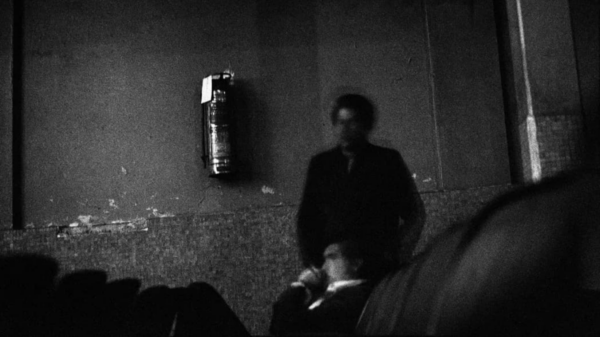

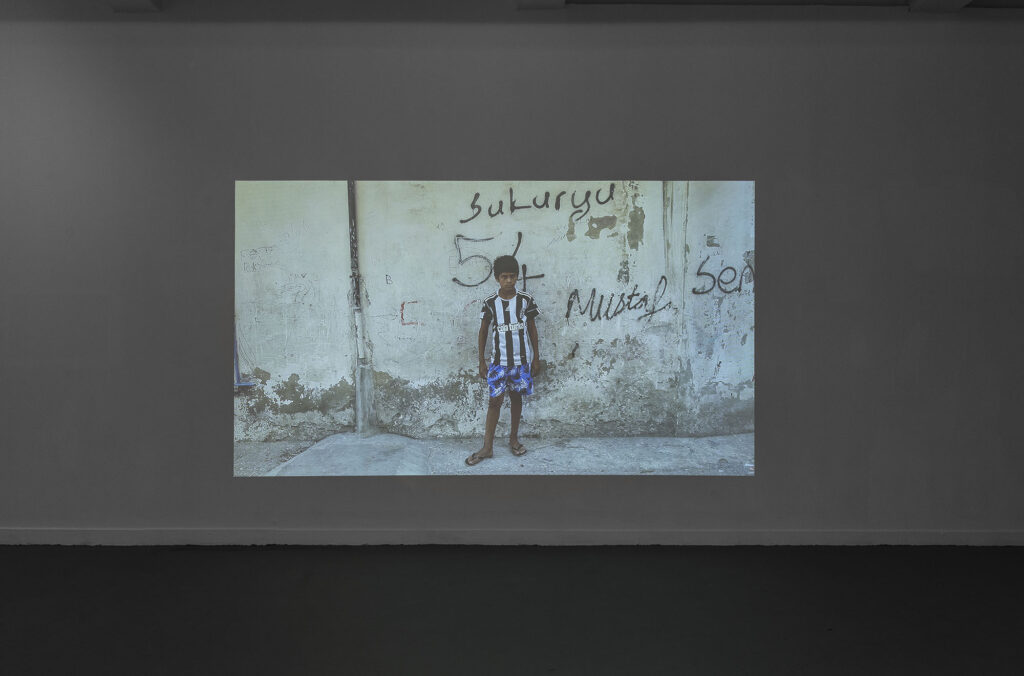

The supposedly dichotomous media of “the still image” and “the moving image” are in fact the same, as video is a set of still images which are projected in high velocity. The moving image, the simulacra of the flow of time, is composed of a set of fragments, a series of still photographs which leave some blanks between them – some unrecorded moments of time. The Unspectacular from 2012 by Volkan Kızıltunç is a video which operates under the logic of still image. In this work, the artist focused on individuals living in gentrified neighborhoods in Istanbul, Nevşehir and Trabzon, cities with high concentrations of city renewal projects. The residents stand in front of their soon-to-be-demolished houses or those that have already been reduced to ruins. Kızıltunç asked his subjects to look straight ahead and pose for still-photographs, but instead shot a long exposure on video. While the wind is blowing, the animals are moving and time goes on, they hardly move. While they strive to stand still, their life circumstances are being transformed. Karl Marx claimed that the prime goal of production is the “annihilation of space by time”,[1] i.e., the acceleration of the movement of produces between markets. It is the on-going movement of capital which is the catalys of the transformation that The Unspectacular captures: the poor are moving out, the rich are moving in.

The composition of The Unspectacular – people standing in their natural habitat – is a recurrent motif in historical portraiture. The 17th century painter Anthony van Dyck, for instance, often painted English aristocrats against the backdrop of their residence or lands. Van Dyck’s deep compositions, composed by a single figure or a small group of figures standing firm in front of an artificial or natural landscape, make clear that the surroundings are metonyms of the figure, especially in regard to its public persona and financial might. Likewise, The Unspectacular backdrops of the protagonists of Kızıltunç’s film are reflections on their masters’ lives, on what is now and what was lost. Trying to hold on to a moment – to stand still as directed by the artist – is revealed to be a lost cause: the subjects often blink, look another way, move their fingers gently or cough. The bulldozers of time are at work.

Throughout most of the film, the unspectacular people look us straight in the eye, and we spend longer time looking at them than we would with most strangers we notice on the street. And as we look at an image of a single person for 15-20 seconds looking back at us, a sense of familiarity infiltrates, and some thoughts and associations that go beyond the perception of an image but to a reaction to another human being emerges. Kızıltunç’s protagonists draw much attention through their gazes, prolonged and intensified by the change of medium from a still-image to a moving-image (that to say, a series of still-images projected for around 9 minutes). The gaze is a medium of dialogue, involving two subjects who recognize each other’s subjectivity by looking at one another; and the longer you look, the deeper you see.

Therefore, the people in The Unspectacular are at the same time singular human beings and signifiers of social order. While looking at each portrait for 15-20 seconds, we observe unique features and tendencies; but the assembly of the individuals into a group of people, whose common denominator is of losing their homes, is a reference to social status.

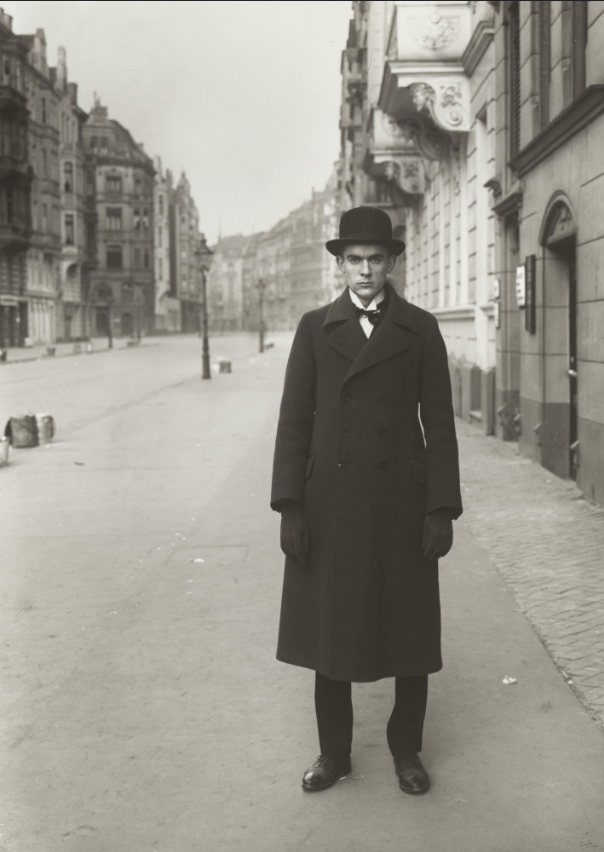

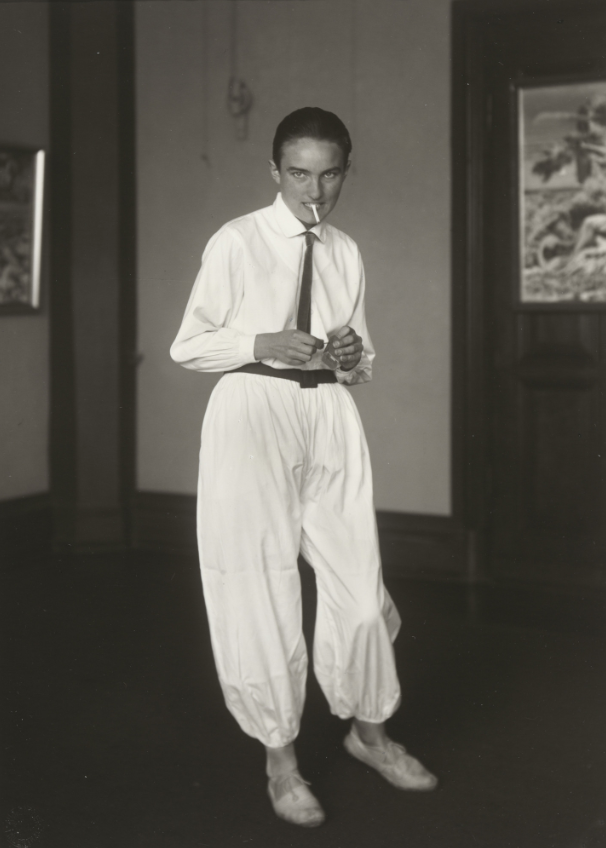

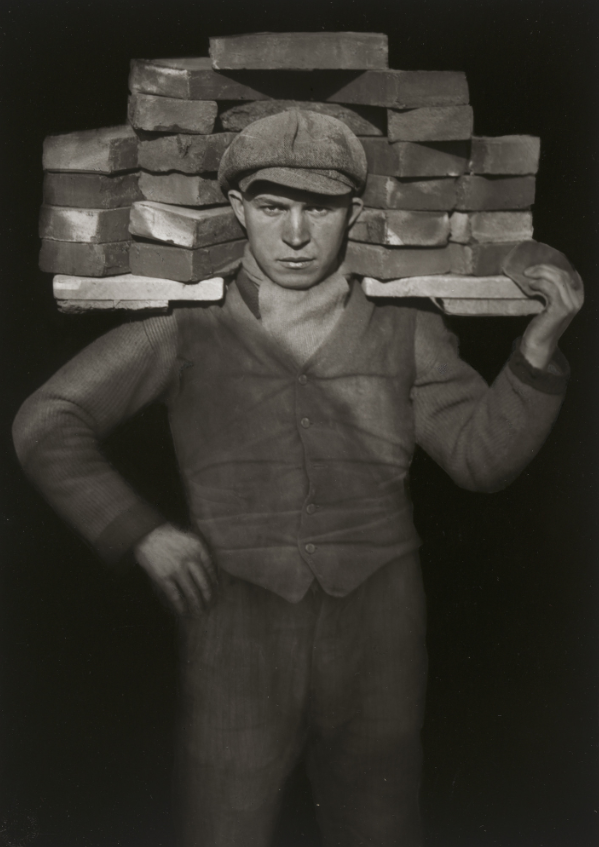

This mix of the private with the communal – or better to say, the private within the communal – is reminiscent of the photography by August Sander. August Sander (1876–1964), one of the most influential and innovative photographers of the early 20th century, worked for about forty years on the groundbreaking project People of the 20th Century (Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts): a monumental corpus of photographs consisting of more than 600 portraits of men and women in their work environment. The photographed subjects, documented throughout Germany, stand in the center of the composition, looking directly at the camera, as if to say, “I am here.” In a lecture from 1931, Sander said that with this project “I attempted to arrive at a physiognomic definition of the German people”,[2] and later elaborated on what physiognomy means:

We know that people are formed by the light and air, by their inherited traits, and their actions, and we recognize people and distinguish one from the other by their appearance. We can tell from appearance the work someone does or does not do; we can read in his face whether he is happy or troubled, for life leaves its trail there unavoidably.[3]

Sander’s physiognomic study addresses genetics, psychology and sociology – inherited traits, feelings, and interestingly, also labor. The latter is closely connected to the arrangement of the portraits in the corpus. While the images themselves celebrate individuality, Sander’s subjects are arranged within the corpus according to typological criteria: the labels accompanying most of the photographs do not indicate their names, only their occupation, and are grouped into peasants, farmers, artisans, bourgeois, homeless, and so on. The result is a series of portraits depicting individuals with a certain genetic baggage and private feelings. Each of them is defined and identified by virtue of their part in the greater social system; portraits of individuals who together make up a portrait of German society in the days of the Weimar Republic. For his introduction to Sander’s 1929 Book Face of Our Time (Antlitz der Zeit), Alfred Döblin commented on Sander’s ability to photograph a unique human being and a member of social class at the same time:

As we are human beings, we only concern ourselves with individuals – with humans. With coloured people we already find it more difficult. If we were elephants, we would divide humans, I mean at the zoo, into those who just walk past and those who give us sugars; the keepers would form their own group, a particular species of human. Looking at human beings, i.e. at ourselves, in this way, has enormous advantages. It is not necessary to take the elephant’s point of view, the distance conferred by a scientific viewpoint or a historical viewpoint, or a philosophical or economic one, would be sufficient.[4]

Sander’s works were a fundamental source of inspiration for The Unspectacular by Kızıltunç, and similar to Sander, he is providing the observer with the opportunity to look at other people simultaneously as a person and an elephant. In fact, The Unspectacular could be read as a version of People of the 20th Century: it is Turkey rather than Germany, the people come from similar social strata rather than the whole array of German social order, and video replaced by still photography – but the underlining tone is similar, i.e. that despite the unique skills and powers of each individual, man is a social creature, and people’s abilities are the outcomes of their affiliation with the environment and class that dictate their life circumstances.

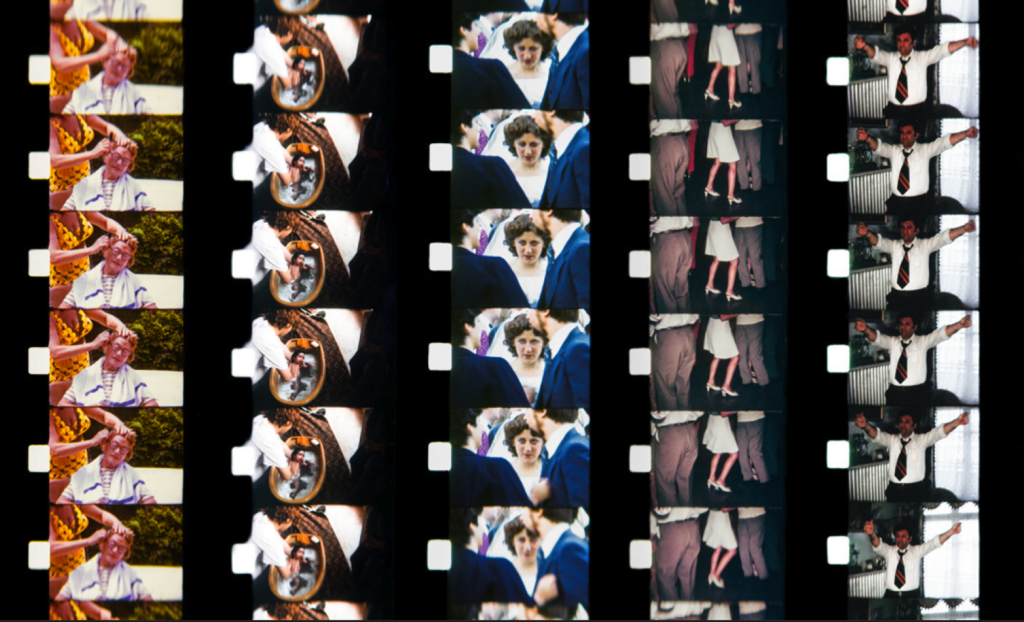

But the change of medium from the still image to the moving image introduces another element, and that is of temporality. Sander’s images are icons, eternal though addressing a specific time and place. The movement of the image – an image which aspires to be still – is a reflection about what has just had been and now lost. It is a study of the present that is overwhelmed by history. The baggage of history, along with semiotics, the gaze and the juxtaposition of personal with the public, are also main components of Kızıltunç’s 2014 three-channel video installation, The Look. In this work, the artist used as medium home-videos recorded on film from the 60s, 70s and 80s. The artist used these films, along with discolorations and scratches that are prevalent in old films, and gave them some 50 years later new lives as video-art: a glimpse to times gone.

From the original material, Kızıltunç extracted moments in which family members look at the camera, thereby transforming these moments of familiarity – the eye contact between relatives – into moments in which the filmed figures observe the viewer. These moments of looking at the camera within a private setting, usually accompanied by a smile to a relative who was holding the camera, are manipulated into gazes upon the unknown observer who is visiting the public exhibition space. And as this stranger looking out from the screen is smiling at us, he is not much of a stranger anymore.

Since its inception, photography had strong links to performance; for instance, the studio photographs from the second half of the 19th century, which placed the European sitters dressed in oriental clothes in an alternative imaginary habitat, such as the Near East. Both The Look and The Unspectacular hold a strong performative aspect in them. It is only natural: the moment that the subject is aware of the presence of the camera, he performs towards the camera; but the manipulation of photographic medium in these works also manipulates the performance. In The Unspectacular the subjects try to perform for a still image, but eventually perform for a video; in The Look, the acknowledgement of the familiar photographer who is holding the home video camera, provoking reactions to him specifically, is manipulated into an interaction with the observer of the work.

The Look takes part in Kızıltunç’s efforts to resurface old neglected films. For his work Gaps of Memory – Istanbul, Kızıltunç assembled nearly 1000 reels of 8 and super 8 mm films, taken between 1965 and 1985. These are home videos of around 50 different families, with films from the Bosphorus and the coastal areas of Istanbul. Kızıltunç studied archaeology in Istanbul University before turning to photography, and indeed acts like an archaeologist, as he unearthed forgotten visual material, studied and presented it. The assembled archival materials, presented in a four-channel video, are transforming the private performance into a public one; hence, the visual study of these materials is not of specific families, but rather of regional history. It allows a reflection upon the architectural, social and economic changes that occurred in the Bosphorus between the 1960s and the 1980s.

But again, typologist Sander creeps in: the fragments of the original films were not grouped chronologically or geographically, but rather according to typology. The work presents fragments of the films in 4 screens, showing different families from different times performing similar actions: families rowing boats, walking along the pier, driving along the coast line, embarking on a boat, jumping into the water, and so on. As in the opening of Anna Karenina: “All happy families are alike”.[5] The observers participate in the visual study of the archival materials: they act as voyeurs of intimate scenes, compare between them and reflect upon their historical context. And then, nostalgic feelings arise, melancholy over happy moments we did not experience. In Gaps of Memory – Istanbul, nostalgia – literally “homesickness” in Greek – is melancholy over lost home, lost origin and lost times. Furthermore, it is melancholy over amnesia, as the artist conceptually represents the lack of remembrance in light of the fragmentation of what survived; a work about the gaps in continual memory which laments over the impossibility of the complete reconstruction of the past.

This artist book, Sonder, further sheds light on the gaps of memory, revealed through the medium of photography. It is an assemblage of still images extracted from 8 and super 8 mm films from the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s from Turkey, Germany, Austria, USA, Italy, Israel and the UK. The artist extracted Images from home videos, hence removing them from their sequence and isolating them from their original context. He further manipulated them by cropping them, treating them as still images whose composition is arranged. It is a study of medium, a revealing of the essence of the moving image as an assemblage of still images, as Kızıltunç returned the videos to their origin of a still images.

Instead of a sequence of time, Sonder offers a sequence of types of memories. Rather than sorting the materials according to time and place, Kızıltunç categorized the images according to their visual types. All happy families are alike, both in different countries and continents. This approach is reflected in the name of the book, Sonder, a word invented by John Koenig for his The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, a dictionary of invented words which defines emotions that don’t have the words to express them:

n. the realization that each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own—populated with their own ambitions, friends, routines, worries and inherited craziness—an epic story that continues invisibly around you like an anthill sprawling deep underground, with elaborate passageways to thousands of other lives that you’ll never know existed, in which you might appear only once, as an extra sipping coffee in the background, as a blur of traffic passing on the highway, as a lighted window at dusk.[6]

And indeed, passersby get as much attention in Sonder as the original objects of the films: the back part of Sonder is dedicated to still-images extracted from the film of people that were not intended to be filmed, but were accidently captured by the camera as they moved by. Kızıltunç’s approach is humanistic, as his work aspires to see every human as a unique and fascinating phenomenon worthy of attention and appreciation, a human who is interconnected to all other humans on the basis of their common humanity.

[1] Karl Marx, Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy (Rough Draft), trans. Martin Nicolaus (New York: Penguin, 1973), 524.

[2] August Sander, “From the Nature & Growth of Photography: Lecture 5: Photography as a Universal Language”, trans. Anne Halley, The Massachusetts Review 19/4 (1978), 677.

[3] ibid.

[4] Alfred Döblin, “Faces Images and Their Truth”, trans. Michael Robertson, in August Sander: Face of Our Time (Munich: Schirmer/Mosel, 1993), 11.

[5] Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina, trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (London: Penguin Books, 2002), 1.

[6] John Koenig, “Sonder”, in The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, https://www.dictionaryofobscuresorrows.com/post/23536922667/sonder.